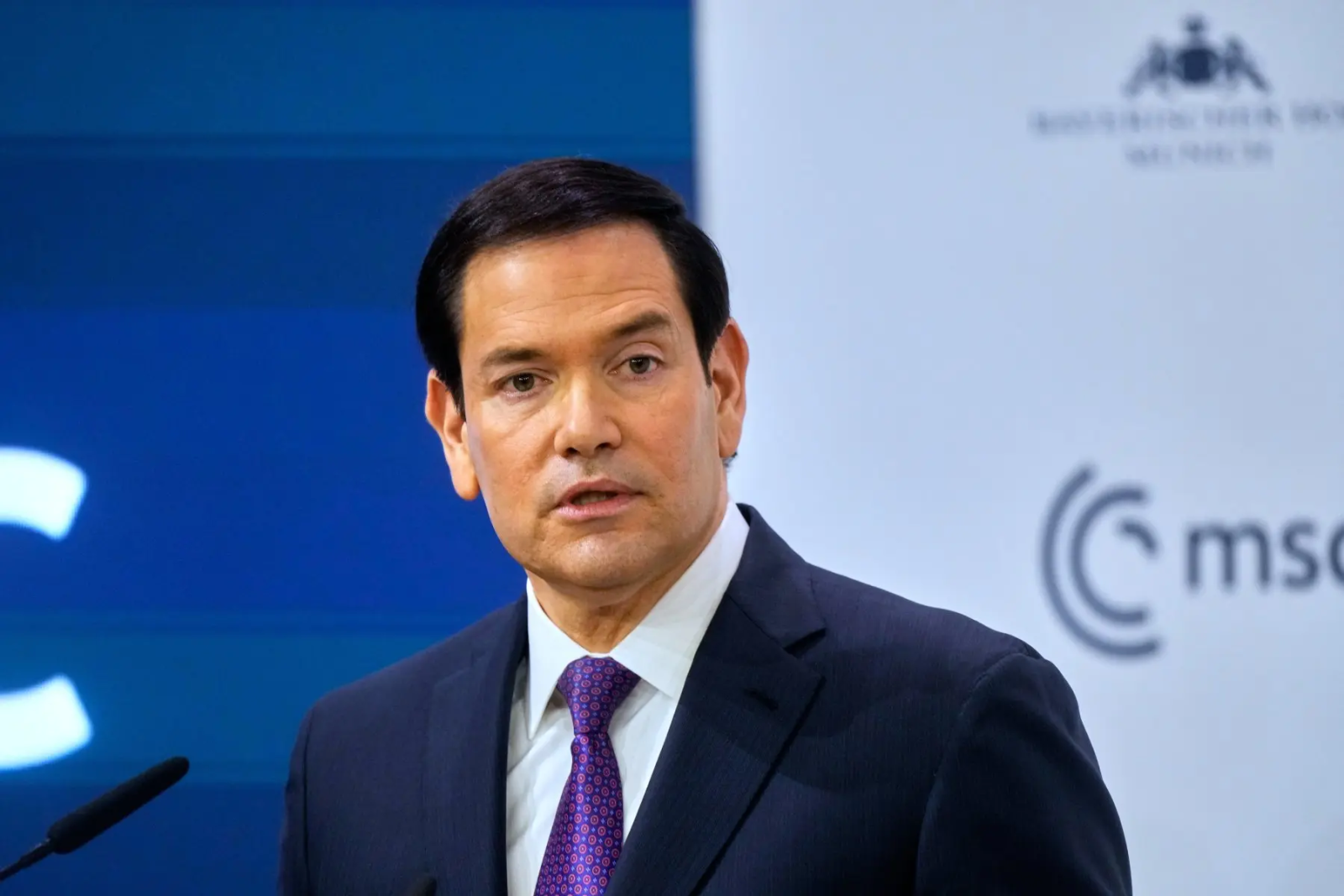

West First, World Later: What Rubio’s Munich Speech Signals for the Global South

Marco Rubio’s Munich Security Conference speech signals a decisive shift in Western strategy toward sovereignty, industrial revival, and civilizational unity. For the Global South, the message is clear: Africa, Asia, and Latin America are no longer peripheral but central arenas of economic and geopolitical competition. The real question is whether this renewed Western focus will produce equitable partnerships or reinforce old patterns of resource extraction and strategic control.

At first glance, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s address at the Munich Security Conference sounded like a reassurance to Europe. From the vantage point of the Global South, however, it read very differently. It was less about partnership and more about consolidation. Less about a shared future and more about preserving Western primacy in an increasingly multipolar world.

For countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the speech offered a clear message: the West is reorganizing around sovereignty, industrial power, and civilizational identity, and the Global South will be a central arena of competition rather than an equal architect of the emerging order.

A Civilizational Narrative That Excludes Most of the World

Rubio repeatedly framed global politics as a struggle to preserve “Western civilization.” He invoked shared heritage, Christian faith, and historical achievements as the glue binding Europe and America together. This framing is powerful domestically, but internationally it narrows the definition of who belongs at the table.

The Global South appears in this worldview not as a community of sovereign actors with diverse interests, but as territory where influence must be maintained. At one point, Rubio explicitly called for a unified Western effort to “compete for market share in the economies of the Global South.”

That phrasing matters. It suggests that developing regions are markets to be captured, not partners to be empowered.

For African economies pursuing industrialization, value addition, and technological sovereignty, this raises a fundamental question: Will engagement with the West be structured around mutual development or around access to resources, labor, and consumers?

The Ghost of Empire in a New Language

The speech’s historical narrative celebrated Western expansion through missionaries, explorers, and empire builders while portraying anti-colonial movements as forces that accelerated Western decline.

From a Global South perspective, this is a reversal of lived history. Decolonization was not a tragedy. It was liberation.

Africa, including Tanzania, continues to grapple with the structural legacies of colonial rule: commodity dependence, artificial borders, and underdeveloped industrial bases. When Western leaders frame colonial retreat primarily as loss, it signals limited willingness to address those structural imbalances.

Calls for allies to be “not shackled by guilt” about the past further reinforce this perception. Many Global South governments are not seeking guilt. They are seeking fair trade, technology transfer, climate justice, and reform of global financial institutions.

Economic Nationalism and the Resource Question

Perhaps the most consequential part of Rubio’s speech was economic.

He argued that deindustrialization in the West resulted from misguided globalization and pledged a push for reindustrialization, supply-chain sovereignty, and domestic manufacturing revival.

On its surface, this is understandable. Every nation wants productive capacity. But for resource-rich developing countries, it signals intensifying competition for critical minerals, energy resources, and agricultural inputs.

Africa holds much of the world’s cobalt, lithium, rare earths, and strategic minerals essential for batteries, semiconductors, and renewable technologies. Tanzania alone is positioning itself as a major player in graphite, nickel, and rare earth elements.

If Western economies seek to secure these inputs while building manufacturing at home, the risk is a familiar pattern: extraction without industrialization.

The key question for African policymakers is whether new partnerships will include local processing, value addition, and skills development, or whether the continent will remain primarily a supplier of raw materials.

Migration Without Context

Rubio described mass migration as a crisis threatening Western cohesion. This framing resonates politically in Europe and the United States, but it omits the drivers of migration.

Many migration flows originate in regions affected by conflict, economic restructuring, climate stress, or governance breakdowns. Some of these pressures are linked to global trade patterns, historical ties, or foreign interventions.

For countries like Tanzania that host large refugee populations themselves, migration is understood less as a cultural threat and more as a humanitarian and development challenge. The Global South hosts the majority of the world’s displaced people, often with far fewer resources.

A purely securitized approach risks addressing symptoms rather than causes.

Climate Policy and Development Tensions

Rubio criticized Western climate policies as economically self-imposed constraints, suggesting a pivot toward energy security and industrial competitiveness.

For developing countries, this raises a dilemma. Many African states contributed little to historical emissions yet face severe climate impacts, from droughts to flooding. They also need energy expansion to industrialize and lift populations out of poverty.

If major powers prioritize fossil-fuel growth while expecting the Global South to limit emissions, tensions will intensify. Conversely, if climate finance and technology transfer accelerate, a balanced pathway could emerge.

The direction remains uncertain.

Multilateralism Under Pressure

The speech also expressed skepticism toward international institutions, arguing that bodies like the United Nations have failed to resolve major conflicts and should not constrain national interests.

Global South countries have long criticized these institutions for unequal representation and power imbalances. However, they also rely on them as platforms where smaller states can exert influence collectively.

If great powers increasingly bypass multilateral frameworks in favor of unilateral or bloc-based action, weaker states could lose one of their few diplomatic equalizers.

Competing in the Global South

Rubio’s most candid statement was the call for a unified Western effort to compete economically in developing regions.

This reflects a broader geopolitical reality: Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America are now central to global growth, urbanization, and resource supply. Infrastructure projects, digital platforms, energy investments, and defense partnerships are all expanding rapidly.

China has invested heavily through the Belt and Road Initiative. India, Türkiye, Gulf states, and others are also deepening engagement. The West is signaling that it does not intend to cede this ground.

For countries like Tanzania pursuing Vision 2050 ambitions, this competition can be advantageous if managed strategically. Multiple suitors create bargaining power. The challenge is converting interest into sustainable development outcomes rather than short-term gains.

A World of Blocs or a World of Bridges?

Rubio’s speech points toward a future defined less by universal rules and more by competing coalitions. Civilizational identity, strategic autonomy, and industrial strength are replacing the language of globalization and convergence.

The Global South is unlikely to respond by aligning exclusively with any single bloc. Most states prefer strategic non-alignment, diversifying partnerships to maximize autonomy and opportunity.

For Tanzania and its neighbors, the emerging question is not “Which side?” but “On what terms?”

Can partnerships deliver infrastructure without debt traps, trade without dependency, security without loss of sovereignty, and investment without environmental degradation?

What This Means for Tanzania

For Tanzania specifically, the implications are both risks and opportunities.

The country’s mineral wealth, strategic location on the Indian Ocean, expanding infrastructure network, and growing population make it increasingly relevant in global supply chains. Western reindustrialization efforts will heighten interest in East African resources and logistics corridors.

At the same time, Tanzania’s long-standing foreign policy tradition emphasizes non-alignment, South-South cooperation, and regional integration through the East African Community and the African Continental Free Trade Area.

Navigating great-power competition while maintaining policy independence will be the central diplomatic task of the coming decades.

The Bottom Line

Marco Rubio’s Munich speech was not primarily about Europe. It was about the future of power.

It signals that the West is moving toward a more assertive, interest-driven posture grounded in sovereignty, industrial strength, and cultural identity. For the Global South, this confirms that the era of assumed Western stewardship of globalization is over.

What replaces it will depend largely on how developing nations leverage their resources, markets, and diplomatic agency.

The Global South is no longer merely the stage on which great powers act. Increasingly, it is becoming the decisive audience that determines who succeeds.