Why Tanzania Is Missing From Africa’s Startup Capital Map And What Must Change

Tanzania startup funding, venture capital Tanzania, African startup investment, Kenya startup ecosystem, East Africa tech funding, Tanzania fintech regulation, mobile money interoperability, African venture capital, startup law Tanzania, Dar es Salaam tech scene

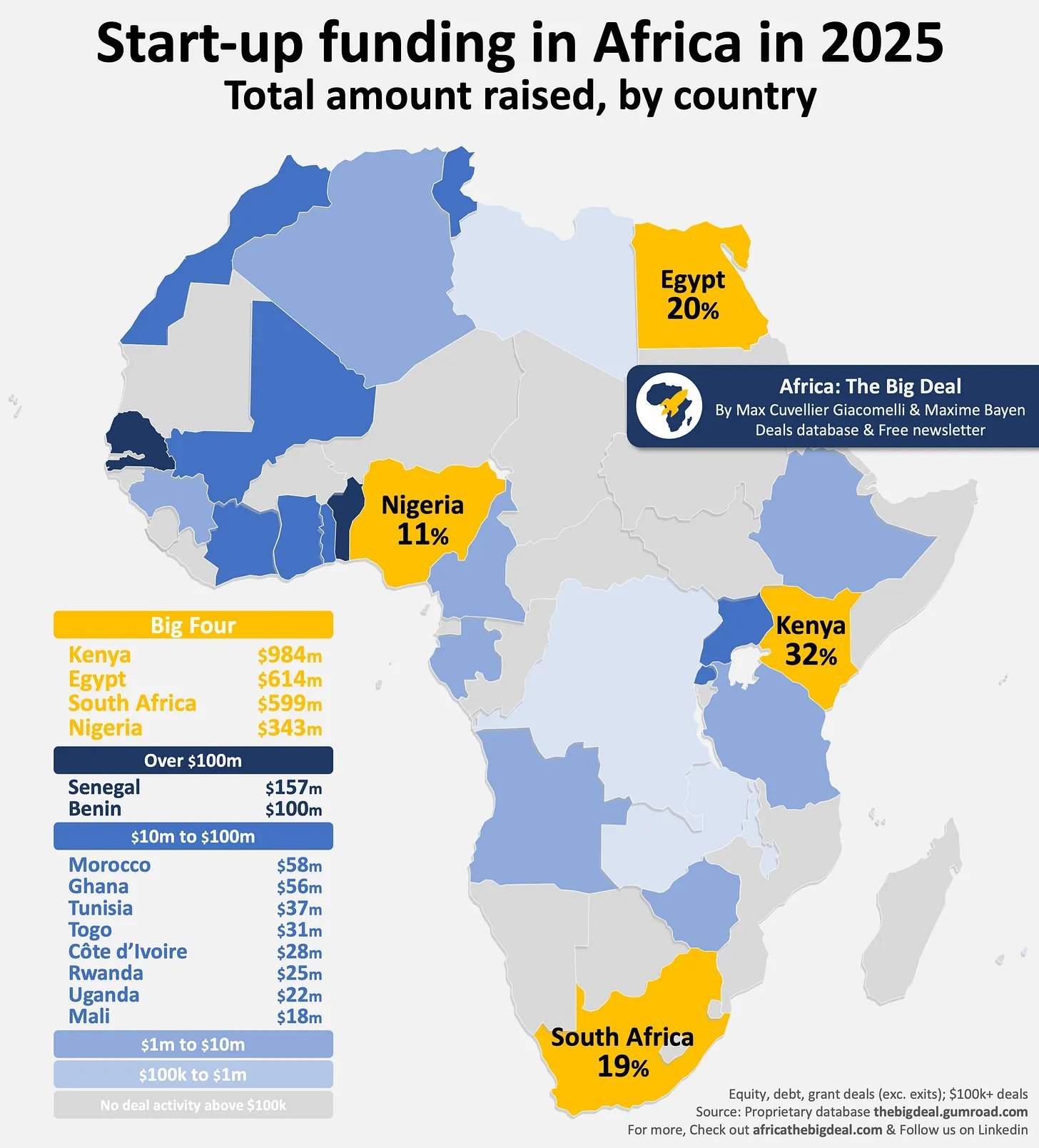

The 2025 African startup funding map reveals something uncomfortable for Tanzania. While Kenya raised nearly USD 1 billion, Egypt more than USD 600 million, and South Africa and Nigeria hundreds of millions more, Tanzania sits close to the bottom, despite being one of East Africa’s largest economies and fastest growing populations.

This gap is not about talent. It is about systems that capital trusts.

Venture capital does not flow to countries that have ideas. It flows to countries that have financial rails, legal predictability, and scalable digital infrastructure. Tanzania currently underperforms on all three.

Payments are where the problem starts

Kenya’s dominance in African venture capital is closely tied to the maturity of its digital payments ecosystem. M-Pesa in Kenya is not just a wallet. It is a deep financial platform that allows people and businesses to send, receive, store, borrow, and integrate money into software systems. Startups can plug into payment rails that are predictable, widely adopted, and tightly integrated with banks, merchants, and consumers.

Tanzania does have mobile money. In fact, Tanzania pioneered mobile money interoperability, allowing users across networks to send funds to one another. That is a major achievement. But interoperability alone is not what venture capital looks for.

What matters to startups is whether they can build low-friction, software-driven businesses on top of those rails. In Tanzania, merchant payments, cross-network fees, API access, compliance requirements, and settlement structures are still more fragmented than in Kenya. A user can send money to another user easily, but building a nationwide digital marketplace, subscription business, or fintech platform on top of mobile money is still costly, complex, and slow.

That friction matters. Venture-backed startups must scale fast. When payments are not seamless for merchants, developers, and financial integrations, growth becomes expensive and unpredictable. Investors notice.

Capital must be able to come in and go out

Kenya, Egypt, and South Africa attract capital because investors believe they can exit. They have legal systems that allow venture funds to hold equity, convert debt, list companies, sell to multinationals, and repatriate returns.

Tanzania remains structurally difficult for venture capital. Currency controls, weak startup law, uncertainty around shareholder rights, and unclear rules on offshore holding structures make exits harder. An investor might believe in a Tanzanian startup, but still refuse to invest because they do not believe they can ever get their money out.

Venture capital is not risk-averse. But it is trap-averse.

Regulation treats startups like banks

In Kenya and Rwanda, regulators created sandboxes that allow fintech, healthtech, and digital businesses to test products without being crushed by compliance designed for large institutions. Tanzania still regulates startups as if they were fully grown banks, telcos, or utilities.

That means:

High licensing costs

Slow approvals

Unclear digital finance rules

Heavy reporting burdens

These are not fatal to corporations. They are fatal to experiments.

The missing narrative

Global investors do not wake up thinking about Dar es Salaam. They think about Nairobi, Lagos, Cairo, and Cape Town. These cities invested in becoming visible to global capital through demo days, accelerators, policy reforms, and diplomatic startup promotion.

Tanzania has not done this. As a result, even strong Tanzanian founders struggle to get into the rooms where capital decisions are made.

Rwanda, with a fraction of Tanzania’s population and GDP, raised more venture funding simply because it built a credible investor story and regulatory pathway.

What Tanzania must do

The path forward is not copying Kenya’s branding. It is fixing Tanzania’s financial architecture.

First, mobile money must become merchant-friendly and developer-ready. Interoperability must extend beyond user-to-user transfers into low-cost, API-driven business payments that allow startups to run digital platforms nationwide.

Second, Tanzania needs a Startup and Venture Capital Law that protects minority shareholders, allows convertible notes, permits offshore holding companies, and guarantees repatriation of profits.

Third, the country must create regulatory sandboxes for fintech, healthtech, agritech, and mobility so startups can test and scale without being regulated out of existence.

Fourth, Tanzania must market itself. Capital follows stories, and stories follow governments that show up.

The bottom line

Africa’s startup boom is real. But it is not evenly distributed. It flows through financial systems, not through patriotism.

Right now, Tanzania is not losing because it lacks entrepreneurs. It is losing because its digital finance, legal infrastructure, and investor pathways are not designed for venture capital.

That is not destiny.

It is design.